Two years ago, Alu Ibrahim, 30, fled civil war in his native country Sudan to seek refuge in the United States. Following U.S. immigration law, Ibrahim identified himself as an asylum seeker to immigration officials and was detained immediately at an airport in Texas.

After spending two years in detention, Ibrahim begged a Texas immigration judge to send him back to the war-torn city of Darfur, Sudan.

“I told her ‘I can’t do it anymore, I want to go back,’” he said.

Ibrahim was released from detention on Oct. 31 and is living in Casa Marianella, an emergency shelter for adult immigrants in Austin, Texas, while he awaits deportation.

On any given day more than 33,000 immigrants, including children, are kept in prisons across the country, costing taxpayers billions of dollars annually. Detention as a tool for immigration management has been deemed inhumane and costly by immigration activists across the country. They are calling on the government to adopt more of what are called Alternative to Detention, or ATD, programs and amend their existing programs to make it more effective.

Casa Marianella currently houses 35 immigrants according to its Director Jennifer Long. Not all are asylum seekers, she said. Some are escaping domestic abuse in the United States others are homeless.

“There are many people in detention who do not need to be,” said Michelle Brané, director of the Detention and Asylum Program based in Washington D.C. “There are many things that can be done to ensure compliance that fall between detention and release.”

These measures she said includes supervised release, open accommodation especially for those fleeing torture or persecution as well as the provision of attorneys and interpreters, so that people can have a better understanding of the process. In riskier cases, the use of ankle bracelets and electronic monitoring is also recommended by Brané’s organization in a handbook for preventing unnecessary detention.

“If you provide people with the resources and information to comply with appearances in court they usually do,” Brané said.

The handbook outlines a four-step process that begins with the assumption that a person does not need to be detained. This will prompt an immediate screening process to assess whether the person is a danger to the community or a flight risk. It also assesses vulnerabilities such as medical conditions, whether this person is a sole caretaker of a dependent or if that person is a parent, an elderly person or fleeing persecution.

Enforcing compliance with immigration hearings is the main reason for detention. But a 93.8 percent compliance rate was achieved for persons in the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Department or ICE’s alternative to detention program, according to their 2012 budget report to Congress.

But not all persons in the immigration debate are convinced that alternatives to detention are the best course of action.

“From my perspective, if you are going to release on bond or on an ankle bracelet you might as well just release,” said Jessica Vaughan director of policy studies at the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington D.C. “A person can just cut off the ankle bracelet or forfeit the bond. I’m not sure what value it will provide to immigration agencies.”

Most of the people identified by ICE do not have a chance of winning their cases and are likely to flee, Vaughan said.

In 2010, more than $2.55 billion was spent on detention and removal operations according to data from ICE.

While ICE does have some alternative detention programs, most persons are detained in facilities that were built and operate as jails or prisons for convicted felons. As a result, the costs of care, custody and control of the population carries more costs than necessary, a 2009 ICE report found.

Community-based supervision and alternatives to detention were also recommended in this report.

Alternatives are more cost effective, Brané said. She estimated that over $100 a day is spent on each detainee. Her organization’s research shows that alternative methods costs as little as $5 per day, per detainee.

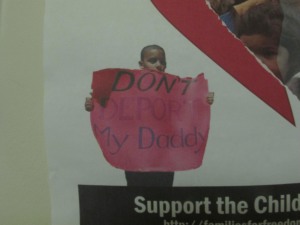

Currently, detention is the first step when an undocumented person is identified by ICE officials. Brané said this can have dire consequences, especially for immigrants with families.

“In some cases if you tell them [ICE officals,] that you have a child, they might release you,” she said. “Children are sometimes left in very unsafe circumstances.”

The mental health of detainees, especially those who may be torture survivors is also a major concern, said Leslie Vélez, director of Access to Justice, a unit of the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service in Baltimore.

“It’s inappropriate, especially if there’s other solutions for detaining someone,” she said. “Even to satisfy mandatory custody, detention does not have to mean county jail.”

Posted on December 1, 2011

0